Similarities between The Happy Hollisters and the Mystery of the Totem Faces and The Hardy Boys Mystery at Devil’s Paw

“Dad!” Joe cried excitedly. “May Frank and I go to Alaska?”

“Just like that?” Fenton Hardy chuckled.

“Better than that. How would you all like to come with me?” Uncle Russ excitedly said his company owned a large airplane which carried many passengers and had two pilots. “I may have the use of it to fly to Alaska and back,” he said, adding that the plane could carry them all if they would like to go.

Wait a minute . . . what on earth is Uncle Russ Hollister doing in a scene with Frank and Joe Hardy? Did The Happy Hollisters and the Hardy Boys take a trip to Alaska together?

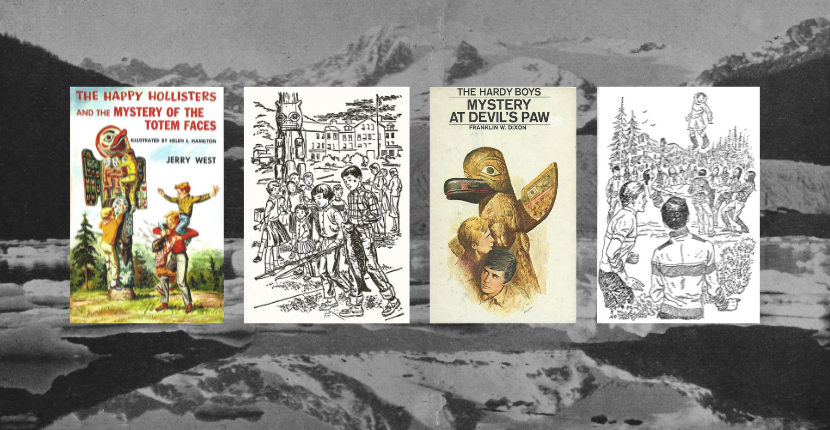

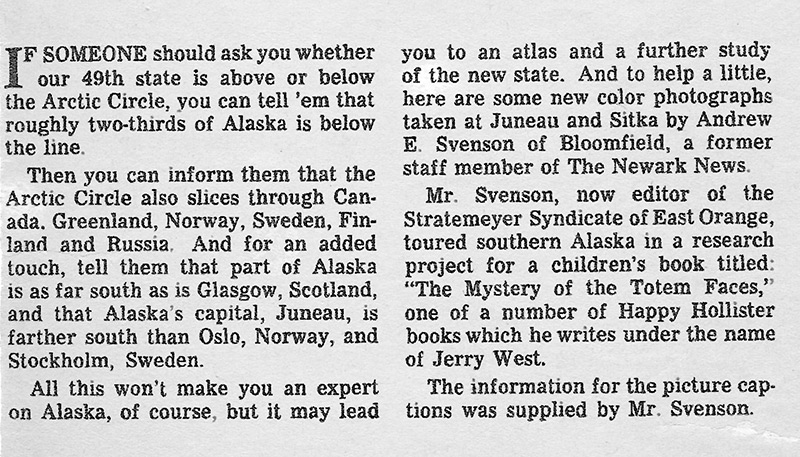

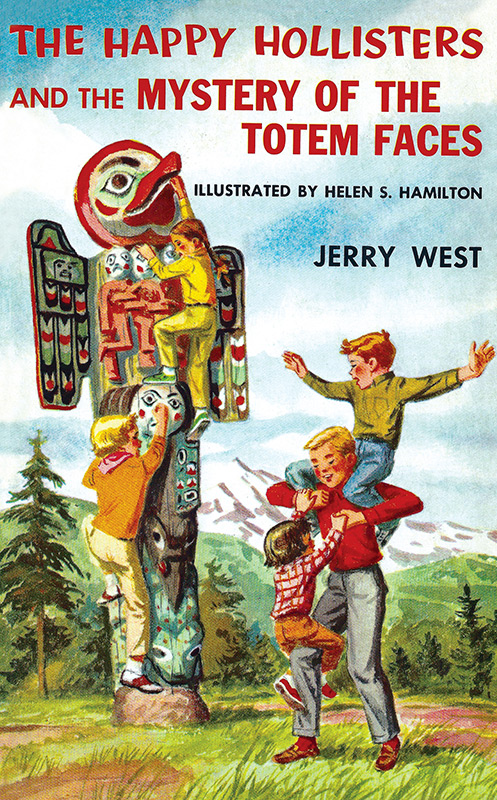

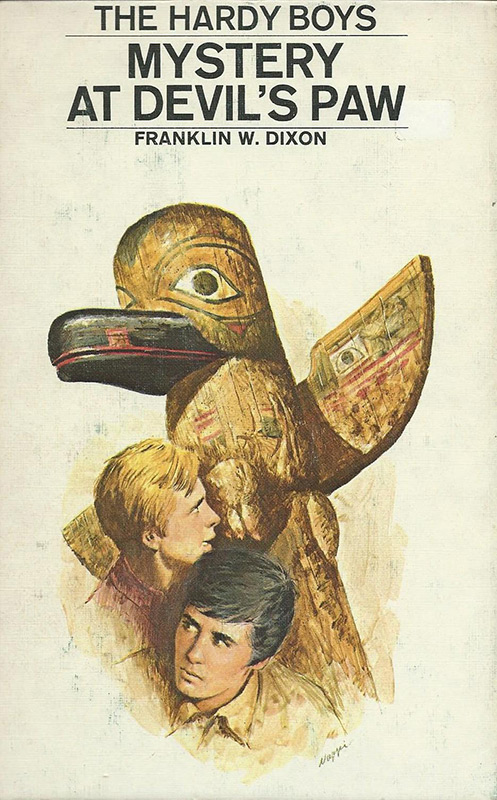

The excerpt above is a fictional mash-up, but if you’ve read The Happy Hollisters and the Mystery of the Totem Faces by Jerry West and The Hardy Boys Mystery at Devil’s Paw by Franklin W. Dixon, you might have noticed similarities between the two books. There’s a logical explanation! Both of these books were based on on-the-spot research provided by one man, Andrew Svenson.

The Happy Hollisters and the Mystery of the Totem Faces was published on April 3, 1958, nine months before Alaska was admitted to the Union by President Eisenhower. The Hardy Boys Mystery at Devil’s Paw was published on January 1, 1959, two days before Alaska statehood. Early editions of the volume have a notice in the front of the book that reads, “The author proudly dedicates this book to the boys and girls of Alaska, which became our forty-ninth state during the writing of The Mystery at Devil’s Paw.” (This note was removed from the 1973 revision.)

In the mid-1950s, when both of these books were in the earliest stages of their development, Andrew Svenson was a staff writer at the Stratemeyer Syndicate. (He would later become the head of the Boys Series Division and a partner in the Syndicate alongside Edward Stratemeyer’s daughters, Harriet Adams and Edna Squier.) The Syndicate was the driving force behind classic mystery series like The Hardy Boys, The Happy Hollisters, Nancy Drew, Tom Swift, The Bobbsey Twins, and others.

Svenson had by 1956 outlined and/or written seven Hardy Boys volumes (under the pen name Franklin W. Dixon) and written twelve Happy Hollisters books as Jerry West. In order to give these books a true sense of “being there” for his readers, he traveled frequently to visit the locales that hosted the plots and did extensive research into background topics. Svenson’s trips to New Mexico, particularly his time spent at the Pueblo of San Ildefonso, flavored The Happy Hollisters and the Indian Treasure and The Happy Hollisters at Mystery Mountain as well as The Hardy Boys Sign of the Crooked Arrow.

Road construction was a hot topic as well. The Garden State Parkway in New Jersey was excavated within a few blocks of Svenson’s Church Street home in Bloomfield in the early 1950s. Details woven into The Happy Hollisters and the Secret Fort and The Hardy Boys Mystery of the Spiral Bridge reflect his first-hand observation of the road construction. (He even left an “Easter egg” in Spiral Bridge, introducing siblings named Andy and Rick—his own two boys—who live on Church Street.)

Svenson made several research trips to Alaska beginning in about 1954. His research notes figure prominently in both Totem Faces, which he outlined and wrote as Jerry West and in Devil’s Paw, which he outlined with Stratemeyer head Harriet S. Adams. The outline for Devil’s Paw was then assigned to writer James Lawrence, who had revised or written about 10 Hardy Boys volumes using the pseudonym Franklin W. Dixon. Lawrence fleshed out the outline with additional descriptive details and dialogue and produced the final manuscript under contract for the Syndicate.

Andrew Svenson became so enamored of Alaska that he purchased a property on Douglas Island, just across Gastineau Channel from Juneau and had a small cabin built for his family to use on vacations. The scenic wilderness of Douglas Island figures heavily in both books, and many of Svenson’s anecdotes and experiences serve double duty, giving both books a deep hint of realism and adventure from a safe distance!

The connection between the two books is apparent from the get-go, as covers for both volumes (including the 1973 revision of Devil’s Paw) feature totem poles prominently. Andrew’s travel photographs were shared with Helen S. Hamilton, who drew the cover and interior illustrations for Totem Faces, and Rudy Nappi, who illustrated the cover for Devil’s Paw. (The interior illustrations for Devil’s Paw, drawn by Arthur O. Scott, are fairly generic depictions of exciting scenes, but without details that tie them to specific notes or photographs provided by Svenson. An exception would be the drawing in chapter 8 of Devil’s Paw that depicts an indigenous wedding ceremony in great detail.)

In the Devil’s Paw wedding scene, a member of the Haida village is married to a Kotzebue Eskimo (chapter 13). The bride must prove her suitability as a good wife by bouncing on a walrus hide held by six men, much like a trampoline. We could not find any documentation in Andrew Svenson’s papers that cite this particular custom or a personal visit to Kotzebue or to a Haida village. However, since the idea of intermarriage between different indigenous groups is also mentioned in The Happy Hollisters and the Mystery of the Totem Faces, we assume that Andrew Svenson may have witnessed either a wedding ceremony or the blanket toss trial. In chapter 12 of Totem Faces, a new friend of the Hollisters tells them that he is “a Tlingit Indian and his wife a Haida. Between them they knew many strange stories of the southeast Alaskan coast.”

Descriptions of other real locations in both books jibe well with Andrew Svenson’s research photographs and an article he wrote for the Newark Sunday News (Alaska, Our 49th Star). This article was published on January 4, 1959, one day after Alska became the 49th U.S. State. Descriptions in both books of the Mendenhall Glacier, for example, express his fascination with the massive ice form.

Chapter 6, The Hardy Boys Mystery at Devil’s Paw

“Mendenhall Glacier,” the pilot told Frank and Joe. “It’s actually a river of ice.”

The boys gaped at the spectacle. “A river?” Joe echoed. “You mean it flows?”

“Yes, but so slowly you could never tell by the naked eye,” Robbie replied. “I guess creeps might be a better word.”

Chapter 8, The Happy Hollisters and the Mystery of the Totem Faces

“Golly!” Teddy said. “How did all the ice get in here, Dad?”

His father explained that this resulted from an accumulation of snow high on the peaks farther inland. Moving slowly under great pressure, the snow changed to ice which moved at a snail’s pace down the valley.

Both sets of sleuths visit the Alaska Historical Museum in Juneau, which is now known as the Alaska State Museum. In Devil’s Paw, Frank and Joe Hardy “went inside and studied the exhibits. Besides mounted birds and animals, there were Indian and Eskimo jewelry and wood carvings, bright-colored blankets, and baskets woven of fine rye grass.” (Chapter 2)

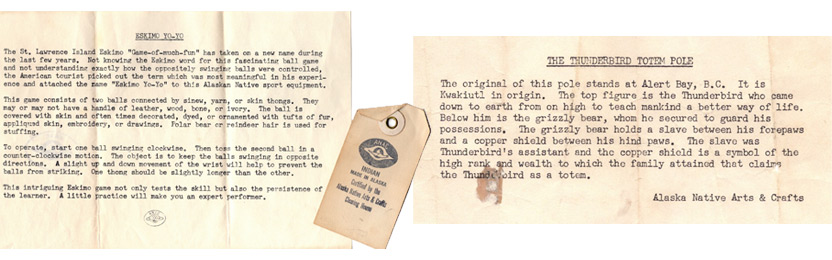

The museum is not named in Totem Faces, but the description is similar: “The museum was filled with native weapons, utensils, works of art, and even a large stuffed brown bear. Ricky and Teddy were especially interested in a kayak made of skin, while Pete and Pam examined several ancient totems.” (Chapter 7) This museum may be where Andrew Svenson purchased a small replica of a totem pole and a toy known as an “Eskimo Yo-Yo.”

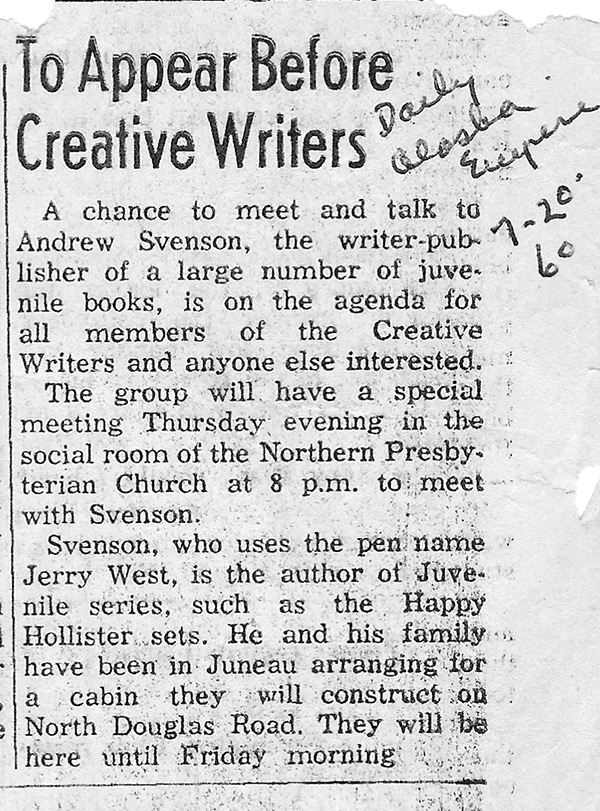

As the Happy Hollisters and Frank and Joe Hardy crisscross Alaska in search of clues, they are all referred to the “Alaska Pioneers’ Home” to talk to old sourdoughs. They learn that sourdoughs are old-timers, “the name given to explorers and gold miners in the far north of Canada and Alaska.” (The Happy Hollisters and the Mystery of the Totem Faces, chapter 1). Andrew Svenson provided a photo of the building to Happy Hollisters illustrator Helen S. Hamilton, and she recreated it in excellent detail in chapter 9 of Totem Faces. It is now known as the Sitka Pioneer Home, an assisted living facility, but it looks much the same today as it did when Andrew Svenson first visited

Chapter 10, The Happy Hollisters and the Mystery of the Totem Faces

“The Hollisters waved good-by and walked toward their hotel, located on the main avenue not far from the waterfront. Across the street from it stood a large building made of tan brick. It sat on a grassy knoll, with sidewalks crisscrossing expansive green lawns.

“In front of the building stood a bronze statue of an old Alaskan sourdough. He wore a battered felt hat and a large mustache. Slung over his back was a load of camping gear. In his left hand he carried a rifle and in his right a walking stick. The statue looked down on several green benches occupied by elderly men chatting in the bright sunshine.”

Chapter 9, The Hardy Boys Mystery at Devil’s Paw

“‘I’ll tell you someone who should know. He’s an old-timer named Jess Jenkins. You’ll find him at the Alaska Pioneers’ Home in Sitka.’

“The brothers boarded a small commercial plane and within an hour were on the lawn that surrounded the Pioneers’ Home in the former Russian capital of Alaska. They found Jess Jenkins sunning himself on a bench in front of the building. The old fellow proved to be a lean, bewhiskered sourdough who had mined gold in both Canada and Alaska.”

Another set of similar scenes that we can attribute to Andrew Svenson’s adventures in Alaska are the encounters with bears occurring in both The Happy Hollisters and the Mystery of the Totem Faces and The Hardy Boys Mystery at Devil’s Paw. In a 1966 interview with the publicity department of Hachette (French publisher), Svenson recounted coming face to face with a bear, but fortunately his wilderness guide was able to “talk” the bear into leaving peaceably. Svenson’s experience had a lasting effect on him; in a 1966 letter to a group of school children to “watch out for bears” if they ever go to Alaska!

The bear incident is much scarier in the Hardy Boys book, which is aimed at a more mature audience: “ . . . Joe was suddenly knocked flat by a huge paw. With a splash, he landed in the water! Frank, whirling, saw an enormous brown bear! A menacing growl rumbled from its throat.” Of course, in typical Stratemeyer fashion (sometimes requiring a suspension of belief that is only possible for young, less-jaded readers), Frank “yanked his brother’s arm, pulling him out of the way. The bear’s paw missed Joe by inches!”

The Happy Hollisters’ ursine encounter is much closer to Andrew Svenson’s personal experience—still perilous, but not quite as life-threatening. “Crashing toward her from among the trees was a towering brown bear. Sue was directly in its path! . . . The animal continued his headlong rush. But after lumbering into the clearing, he stopped and stood up on his hind legs. ‘Yell! Holler! Make all the noise you can!’ Chief Harris cried out.

Svenson’s first-hand experiences lend an immersive authenticity to his books and offer a fun way to introduce young readers to the wonders of Alaska. Little factoids are sprinkled liberally through both books that may encourage readers to read further about the territory and how it was established. From background information on the purchase of the territory in 1867 from Russia to the design of the state flag by a 13-year-old boy in 1927, there are little bits of knowledge that children absorb without feeling like they’re reading a textbook.

In 1970, Svenson told a reporter from the Charlotte Observer, ““While children read for excitement and entertainment, the books fill them in on facts. They’re educational but children don’t know it.’ A book set in Alaska, The Mystery of the Totem Faces, drew praise from an Alaska museum curator, who called it the best work on totems written for children.’”

The Happy Hollisters and the Mystery of the Totem Faces also received praise from grownups in Alaska. Genevieve Mayberry, Juneau author of Eskimo of Little Diomede wrote that “I just finished reading The Mystery of the Totem Faces and must write and tell you how much I admire it.” Quincy Belle Snow, R.N., who was a nurse at the Mt. Edgecumbe Hospital in Sitka, wrote “You have done such an excellent job of weaving fact and fiction together. So much of it is real Alaska. . . Tell Helen Hamilton that her illustration adapted from the snapshot is really good . . .Your book has certainly been well received in this area.”

Back in the 1950s, travel to Alaska was considered quite exotic, and Svenson was a lucky man to have a research and travel stipend provided by his employer. Alaska is much more accessible now as a tourist destination, and surely Andrew Svenson would be thrilled to know that his books are still enjoyed by young readers who may benefit from his experience and be able to follow in his footsteps to explore the 49th state.