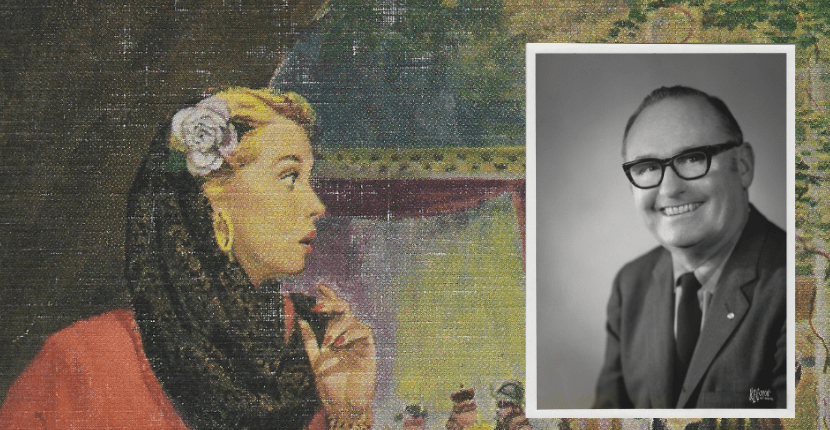

The Shocking Secret of Nancy Drew’s Success (According to Stratemeyer Syndicate Partner Andrew Svenson)

Andrew Svenson, who wrote The Happy Hollisters under the pseudonym Jerry West, was also involved with the production of the Nancy Drew books as a partner, editor, and writer in the Stratemeyer Syndicate. He wrote the outline for volume 30, The Clue of the Velvet Mask, which was then written by Mildred Wirt Benson under the pseudonym Carolyn Keene. The following is the text of a speech about Nancy Drew that Andrew Svenson gave to his Rotary Club in 1972.

Speech about Nancy Drew

delivered to the E.O. [East Orange, New Jersey]

Rotary Club

February 7, 1972

I wanted to direct this discussion to the women in the audience, because Valentine’s Day is a day of reminiscence. And what I want you to do is to reminisce with me about the girls’ books which you read many years ago. Times have changed in the American literary field both for adults and children.

Basic ingredients of story telling are, of course, the same, but how you tell it is different. Do you remember the Camp Fire Girls? They were brought out in the first years of the twentieth century by Hildegarde G. Frey. They were not pertily [sic] pretty. These 18- and 19-year-old girls had grown-up good looks. They glowed with good health from their outdoorsy activity. But at the same time, they were entirely feminine, the kind of healthy femininity which disappeared with the beginning of the jazz age.

The campfire girls carried on a guerilla war against both the Boy Scouts and the Girl Scouts and bested them both in such activities as kite flying contests and girl team activities.

Then there were the Ruth Fielding books. Ruth was a creation of Edward Stratemeyer, who started the business in which I am now a partner. He wrote under the pseudonym this time of Alice B. Emerson. Ruth was identified with theatrical enterprises and was invariably successful in her field. I know there are other books you liked, especially you younger women, who remember Connie Blair and Beverly Gray. Then there were Vicky Barr, the airline stewardess, and Cherry Ames, the crisp, efficient nurse. We, at the Syndicate, added another one to that list, Linda Craig, girl on horseback. It seemed like a winning combination. But Linda and her horse never got off the ground.

The big star in girl literature, although some librarians don’t like to call it that, is Nancy Drew, and more about her later. But before we go into Nancy’s never-never land, I’d like to mention Judy Bolton. Here was a girl simple and practical, about half a social class below Nancy. She had a brother named Horace, who worked as a newspaper reporter and was very handy to have around at mystery-solving time. Judy is gregarious. She lets her whole gang of chums solve her mysteries. Unlike Nancy, Judy has a very real and red-blooded boyfriend, named Peter Dobbs, a no-nonsense kid. When Judy suspected him of a practical joke, and later found he was innocent, she murmured:

“How can I ever make up for being stupid enough to think it was you?” “Like this,” Peter replied. He kissed her, right in plain sight of all the curious people who lived in that shabby row of houses.”

I want to say that no Stratemeyer Syndicate heroine ever got grabbed and kissed in public like that. Nancy’s friend, Ned Nickerson, whom we will come to later, never had the courage!

I remember once, while editing a Tom Swift story, that I dared to be a little riské [sic]: Tom was taking off to the moon in his space rocket, and his girlfriend was bidding him good-by. More than a handshake was needed here, and I had them embrace. I think that was the only time in Stratemeyer Syndicate history that such a thing had happened!

Remember the Dana Girls? They appeared in 1934, not too long after Nancy’s early success. Louise Dana was 17, her sister 16. One was dark, the other blond. Never in any of our stories have we had two characters with the same color hair. That would be heresy. The girls are relieved of parental interference by living with unmarried Aunt Harriet and good old Uncle Ned Dana, a sea captain. He made frequent voyages away from home. The Dana girls go to a boarding school. This is a carry-over from the snobbish attitude in many of the early books for girls. This, of course, stamps them immediately as upper-middle class.

But the greatest heroine of all, of course, is Nancy Drew. She was conceived of the brain of Edward Stratemeyer not too long before he died. Four books were brought out together in 1930, the first being THE SECRET OF THE OLD CLOCK. This should ring some bells with you women. THE HIDDEN STAIRCASE was second. Up until now more than 30 million copies have been sold.

Although the Hardy Boys were begun three years earlier, they have not reached such astronomical figures. The reason is that girls read more than boys, especially in the 8-11 or 12 age group. Where Nancy sells two million copies, the Hardys will sell a million and a half.

A girl usually gets her introduction to Nancy Drew from someone else. A gift, or a loan from a friend or relative. When the Nancy readers reach epidemic proportions is in the fourth, fifth, and sixth grades. If you don’t believe it, come to our offices some day and I will show you batches of two hundred letters a month which pour in from Nancy fans.

To many parents, and even other publishers, the secret of Nancy’s success is a mystery. Nancy is terribly square, yet she has an appeal to the teeny boppers today just as she had in the 1930’s. This proves, I think, that there is a rock-ribbed streak of conservatism in the 9-11 age group. These kids participate in all kinds of outlandish fads, but deep down underneath they put aside their psychedelic posters and “Legalize Pot” buttons and happily step into the make-believe land of Nancy and her friends.

The books have a timeless quality. This is no accident. It was built into each of the titles. Of course, some things like Nancy’s Roadster and running boards and rumble seats of bygone days survived in the books for many years. But even these quaint anachronisms have now been deleted.

I’ll tell you the secret of Nancy Drew. Any of you who would like to write a book, mark these words. Nancy epitomizes really Women’s Lib, even though the books began many years ago.

Consider this if you will. Recollect the days when you were ten years old, hemmed in by parents, school, restrictions, perhaps a too-plain face and a very flat figure, or teeth that were crisscrossed with orthodontic wires. You read about Nancy, titian haired, 18, pretty, yet very smart. Nancy, a girl who had a lovable lawyer father and a housekeeper. Nancy’s mother passed away when she was very young. This was not an act of God but an act of the author, who wanted her quietly to put away so as not to restrict Nancy Drew’s freedom. Besides all of this, Nancy doesn’t go to school. School is never mentioned. She has two girlfriends, Bess, and George. Now George is a girl, although she has a boy’s name. George is athletic, tomboyish, ready to go on any kind of dangerous mission. Bess is a little plump, very frilly, afraid of spiders and snakes. A good foil for the other two, but always there when needed.

Nancy also has a convertible, or a hardtop, or whatever the sporty car is now. Her lawyer father feeds her mystery cases, and she and the girls are away. Voila!

For logistical reasons, or when a strong back is needed, Nancy has a boyfriend, Ned Nickerson. Ned has been castrated at an early age, or so it seems. Nancy uses him for odd jobs, or as an escort to college dances. Poor Ned. He plays his heart out in the football games, and after the victory dance is over, he’s sitting with Nancy in the moonlight and pops a leading question. Nancy brushes him off, pushes him away, and says, “Ned, let’s change the subject.”

I ask you men sitting here, how would you like to take that kind of treatment? For forty-two years? How would you like to be out-guessed, out-smarted, out-witted, by your best girlfriend? Consider this: A clue appears in an obscure document. To wit:

“George and Bess studied the paragraph to which Nancy had pointed. It was a quotation in old English, and they could not make it out. Nancy, who had learned the works of the poet Chaucer in school, eagerly translated it.”

For all of Nancy’s intellectual attainments, let me tell you, she was quite a girl. She rides and swims Olympic style. With no effort she climbs a rose trellis to the second floor. At 100 yards she plugged a lynx three times with a Colt .44 revolver. I might say, however, that that was in the good old days, when Nancy was hell-bent for leather. Today she doesn’t pack a gun. But she can floor a full-grown lawbreaker with a right to the jaw.

In other words, Nancy is in a fantasy world. Yet a world that could possibly be true. If a young girl is looking for daydreams, let her bury her nose in a Nancy book.

Back in the old days (and I might say that we try to vary the books more in modern times), there was first the anonymous warning for her to get off the case or face dire consequences. Of course, she bravely ignores this. Then, in every story, there is a wild chase. This will have to do, of course, with the withholding of sums of money or jewelry from deserving people by thieves and embezzlers. There are missing wills, treasure maps, hidden rubies, secret codes, long-separated relatives.

But murder is never allowed! Kidnapping, however, abounds in almost every book. Somebody, usually Nancy, is spirited away, bound, and gagged, then abandoned. Rescue is swift. Nobody is ever permitted to die. Even the unlucky lynx which is shot by Nancy in the SECRET OF SHADOW RANCH staggers off into the underbrush, presumably to get well after having learned his lesson.

Violence, in the series, usually takes the form of atrocious assaults on Nancy’s person. Blue Cross and Blue Shield consider Nancy a disastrous contract. She is bludgeoned into unconsciousness so much that someone once said she should be hanging around Stillman’s gym looking for odd jobs. She is struck by lightning, hurled down a flight of stairs, even blown to a plaster wall by a charge of dynamite. None of this seems to have had any effect on her health. She always bounces right back.

In the old days, when you women read the books, the protagonists were usually poor people, honest, but well educated, having seen better days. This was a hangover from the depression era. They were ladies and gentlemen in every sense.

Do you remember the crooks? They were readily identifiable: vulgar, bad temper, and they had the unfortunate tendency to raise their voices to people. Also, they invariably had a poor education. They almost always had red hair or coarse, bushy black hair and had nicknames like Spike, Red, Snorky. They could be further identified by their regrettable preference for checkered suits, yellow overcoats, and elevator shoes. They almost always had a physical oddity, like a long, sharp nose or a missing middle finger.

Such a miscreant once wrote Nancy a letter asking her to meet him alone at the foot of White Street. Trying to solve the mystery, Nancy went there, fool-hardy girl. She was captured, bound and gagged, and shoved into a broom closet. She was eventually rescued by Ned and Mr. Drew. Here is some of the dialogue:

“Are you hurt, Nancy?” her father asked apprehensively. “No, I’m all right, Dad,” she assured him. “But I’m afraid the worst has happened.”

It is characteristic of Nancy that this remark is never for a moment interpreted as meaning that her abductor has taken liberties. Far from it. Her rescuers and readers assume at once, and correctly, that what Nancy means is that the crooks have stolen half of her missing treasure map.

Do you remember the women felons of those earlier books? Usually, they were half of an evil couple. They were hard-faced, overdressed, and talked too loudly. Remember how Nancy and her friends never told lies? Remember how they never smoked cigarettes? Remember how there was no booze mentioned in the stories, except once when a watchman was given a micky by the dastardly crooks.

So, you see, the virtues always paid off. Nancy always wins, she always solves the mystery, and captures the crooks. This is what every 10-year-old wants to happen.

One of the letters written to our organization asked why Ned and Nancy were never married. The answer this young lady received was Nancy is too busy solving mysteries to be thinking of matrimony. But I think there’s a different answer. After all these years of frustration the only thing that Ned Nickerson is good for is cutting out paper Valentines!

As an eleven year old boy at the time this speech was given, I enjoyed the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew pretty much equally. But I told my father once that I thought Nancy was actually smarter. He nodded in agreement and pulled a red covered book out of the bookcase. “Here is someone who is even smarter.” It was the first Judy Bolton mystery I ever read.